Peter Rostovsky © 2025

by David Lehman

My Dinner with Michel Foucault

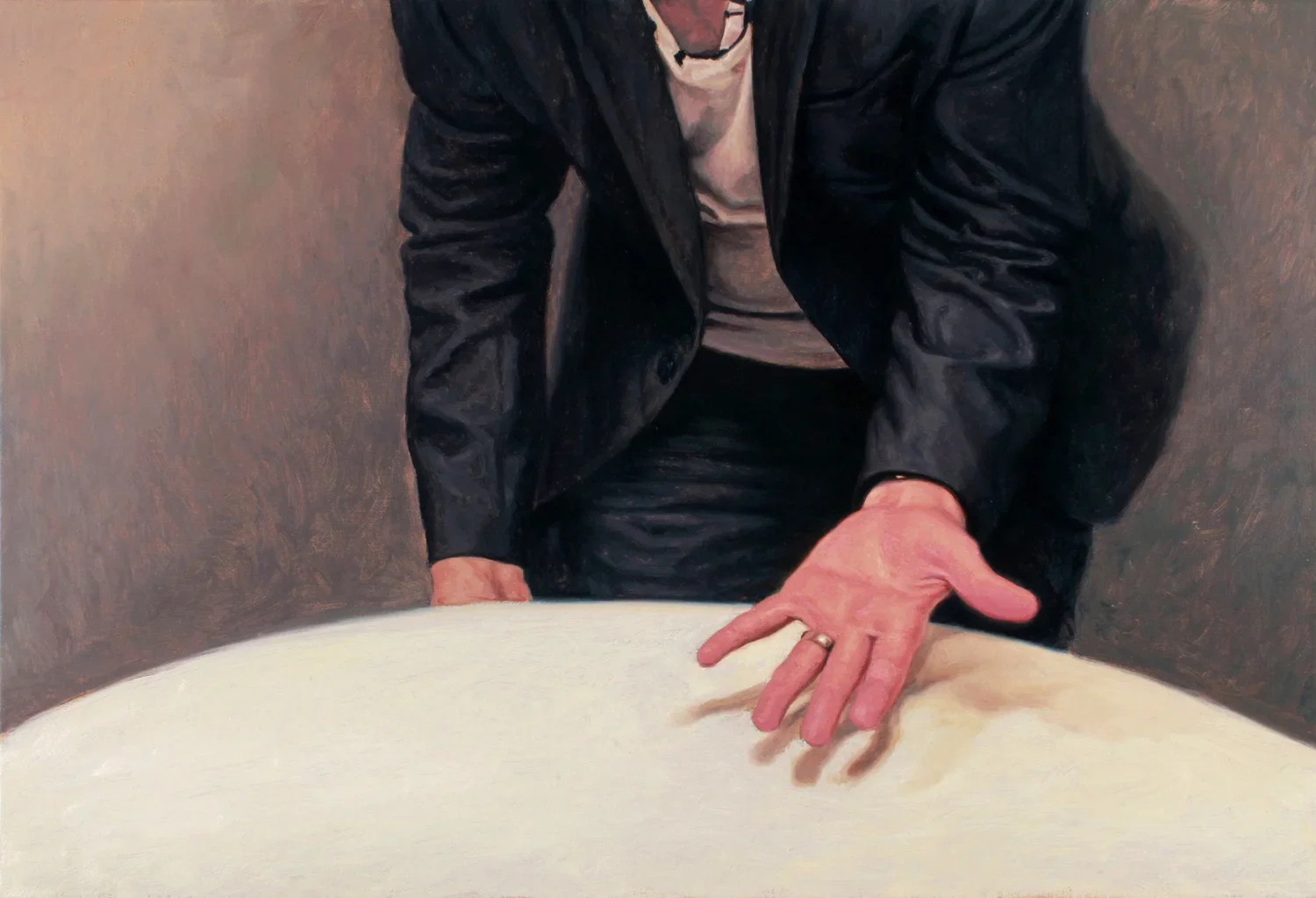

Foucault called me Jack. He called everyone Jack. He called Derrida Jack, not Jacques (Jock), when the two them were on speaking terms, which was jamais. When I visited him in the pen, Foucault told me he hated the esoteric critical vocabulary he was obliged to use. “I hate what they do to my name,” he said. “Foucauldian! Ugh.”

I said “how about so-called limit experiences?”

“That’s just jargon for magazine hacks or campus intellectuals,” he said. “It’s like advertising. It’s really no different.”

“But,” I said, “you did go out into the desert in Nevada and take acid with some guy who didn’t know you had AIDS, am I right?”

“Jack,” he said. “Pipe down. I don’t need this shit from you.”

The waiter came to my rescue with flutes of a crèmant d’Alsace and an amuse bouche consisting of an artichoke paste, avocado, olive oil, and Dijon mustard.

“Relax,” I said, grinned, and waved the prison guard away. I wanted Foucault to enjoy these last few minutes of a brief visit from someone who thought he was important enough to merit such attention. Of all the incarcerated gentlemen in the pen, only Foucault had dining privileges. Because of his fame Foucault’s attorney made French cuisine a part of the deal that saved the state a lot of man hours and paper work and yet seemed to fulfill the exigencies of justice.

“Jack,” he said, with a wink, and I knew he was grateful for the carton of cigarettes I had managed to have delivered to his cell undetected by the panopticon that shone on his bald pate 24/7. Unfiltered Gauloises. While it was illegal to smuggle or sell cigarettes to inmates, possession was not interdicted, and you were allowed to smoke in your cell. “Think of the word cigarette, Jack. It’s the female version of cigar, is it not?” I had to agree though I was all prepared to resist his shtick about the female aspects of the male body, to which I thought the cigarette gambit was leading. But then he surprised me, changing the subject.

“You’re a writer, Jack,” he said. I nodded. “All writers end up mad,” he said. “Why is that? Because they hear voices. You hear voices, Jack. You hear my voice right now. Try to forget me. You can’t. And I’m just one of the voices, one of the scores of voices, even if admittedly a peripheral one. Sooner or later the voices will take over.” And he laughed again, as if Schadenfreude were a virtue.

Dr. Kopf

Dr. Kopf, the old-time Freudian analyst whom I consulted for a record-breaking twenty-two years, smoked a pipe but kept a cigarette box for visitors; he offered me a Lucky, and I took a deep drag. It was then that I had the epiphany that the twenty-first century was an even bigger illusion, and certainly a more malevolent one, than conspiracy fans’ version of the moon landing in July 1969, which we watched on television.

David Lehman’s books include One Hundred Autobiographies: A Memoir and The Morning Line, a book of poems. He is the editor of The Oxford Book of American Poetry and, since 1988, the series editor of The Best American Poetry.